Представлена версия документа, предназначенная для печати

Вы можете загрузить эту страницу на сайте

| |

Cordylophora caspia

Кордилофора каспийская |

Систематическое положение (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Species):

Animalia » Cnidaria » Hydrozoa » Anthoathecata » Oceanidae » Cordylophora caspia

Кордилофора каспийская - Cordylophora caspia, Pallas 1771

Кордилофора каспийская - Cordylophora caspia, Pallas 1771

Русское и английское названия. hydroid; freshwater hydroid, кордилофора каспийская, гидроид.

Синонимы. Bimeria baltica Stechow, 1927; Cordylophora albicola Kirchenpauer in Busk, 1861; Cordylophora americana Leidy, 1870; Cordylophora lacustris Allman, 1844; Cordylophora otagoensis Fyfe, 1929; Cordylophora whiteleggi von Lendenfeld, 1886; Tubularia cornea Aghardh, 1816.

Нативный ареал. Реликтовой понто-каспийский гидроид. Исходное местообитание - Черное и Каспийское моря. Этот вид был впервые обнаружен академиком Российской академии П.С. Палласом в 1771 г. в северной части Каспийского моря.

Современный ареал (мировой и конкретнее в России).

Вид распространился в зонах умеренного и тропического климата по всему миру. Он в массовых количествах обитает в Каспийском море, в опресненных частях Азовского и Черного морей и в лиманах рек. Однако распространение вовсе не ограничивается бассейнами южных морей, кордилофора по Волге и Мариинской системе проникла в Балтийское море (1883 г.), где в силу его малой солености нашла свою вторую родину. У берегов Франции гидроид был обнаружен в 1970 г. Он также встречается вдоль всего атлантического побережья Европы и в устьях всех крупных рек Азии, Америки и Австралии (1885 г.). Этот вид дошел на север до Северного моря (1884 г.), а на юг до Средиземного моря. В Панамский канал гидроид попал в 1944 г.

Первые находки в Северной Америке произошли в штате Массачусетс в 1860 году. В 1870 г. он был зарегистрирован в Северной Америке на реке Скулкилл, штат Пенсильвания, и впоследствии был распространен по всей территории Соединенных Штатов, в том числе в район Великих озер и Гавайских островов. Позже гидроид был обнаружен на западном побережье залива Пьюджет и районе Сан-Франциско около 1920 г. (Cohen et al., 1998; Verrill et al., 1873).

Пути(коридоры) и векторы (способы) интродукции. Гидроид прикрепляется к днищам судов или попадает в балластные воды и таким образом разносится по водоемам. По руслам рек кордилофора проникает иногда довольно далеко к северу, но здесь она не получает полного развития.

Местообитание. Пресноводный и солоноватоводный вид. Кордилофора селится на всех твердых подводных предметах, как неподвижных, так и подвижных. Гидроид прикрепляется к разным типам субстратов – раковинам, камням, дереву и растительности. Этот вид переносит широкий диапазон условий среды по солености, температуры, скорости течения и концентрации кислорода. Этот вид предпочитает сильно опресненные участки моря и живет на небольшой глубине, обычно не глубже 20 м. Однако, высокая толерантность к соли гидроиду позволяет выжить в пресной, солоноватой и соленой воде. При определенных условиях кордилофора может жить и размножаться даже в промышленных системах вод. Кордилофора образует небольшие нежные колонии в виде кустиков высотой до 10 см. Полипы сидят на концах ветвей и имеют веретеновидную форму (размер полипов всего не сколько миллиметров). У каждого полипа 12—15 щупалец, сидящих без строгого порядка в срединной части тела. Свободноплавающих медуз у кордилофоры нет, особи медузоидного поколения прикреплены к колонии. Зимой колонии погибают. Новые колонии на следующий год образуются из корневидных веточек, которыми колония укрепляется на субстрате.

Особенности биологии. Колонии кордилофоры моноподиальные, с терминально расположенными зооидами. Основание колоний прикрепляется к субстрату разветвленной гидроризой. Тело полипа веретеновидное с 12-15 беспорядочно расположенными щупальцами. Степень ветвления, а также размеры гидроида и количество щупалец зависят от условий среды. Скорость роста зависит от температуры, солености, концентрации кислорода, трофических условий. Вся колония (за исключением самих гидрантов) снаружи покрыта перидермом. Свободноплавающих медуз нет, особи медузоидного поколения сильно редуцированы и имеют вид овальных тел, расположенных под основаниями полипов и на ветвях. Размножается кордилофора почкованием, зона почкования находится в основании гидранта, боковая ветвь некоторое время стелется по материнской. Обычно, при бесполым размножении они формируют вертикальные столоны, которые отделяются от колонии, прикрепляются к близлежащему субстрату и формируют отдельную колонию.

С июня по октябрь наблюдается половое размножение. Колонии раздельнополые, гаметы созревают в мешочковидных гонофорах, располагающихся на боковых ветвях колонии. Гонофоры – это видоизменные особи в колониях гидроидных полипов, в которых образуются половые продукты. Каждая вертикальная ветвь может иметь от 1-ого до 3-х гонофоров с 6-10 яиц каждый. При половом размножении оплодотворение наружное. Из зиготы образуется личинка, напоминающая планулу, которая некоторое время (~12 ч) свободно плавает в воде, прикрепляется и дает начало новой колонии.

Влияние вида (на другие виды, экосистемы включая лесную и агроценозы, здоровье человека).

Кордилофора может жить и размножаться даже в промышленных системах вод. Этот гидроид может достигать высокой плотности, засоряя водозаборные сооружения. Он может подавлять местные виды, конкурируя за пищу.

|

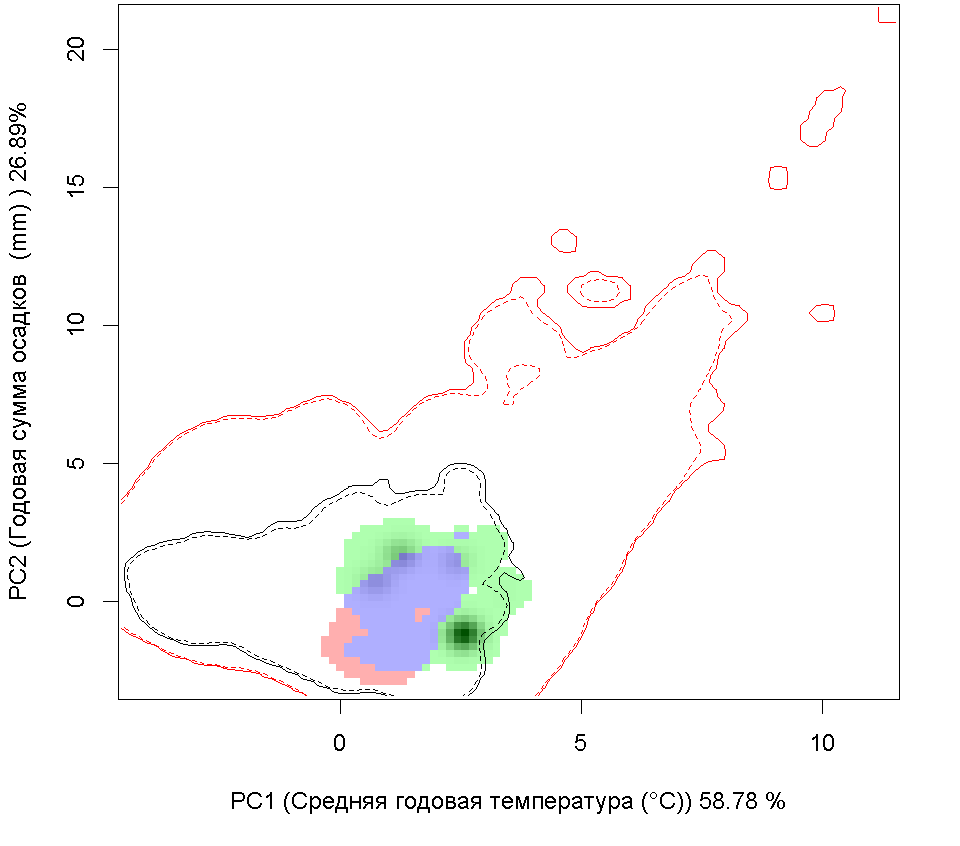

Графическое представление перекрывания ниш нативной и инвазионной частей ареалов, а также при сценариях изменения климата

|

|

Текущий климат

|

|

Нативная часть

|

Инвазионная часть

|

|

A A

|

B B

|

| Графическое представление перекрывания ниш нативной (A) и инвазионной (B) частей ареалов вида, где сиреневый цвет – зона стабильности, розовый цвет – зона расширения, зеленый цвет – зона «неиспользования». Сплошные и пунктирные линии показывают 100% и 90% области доступной среды в нативной (черные линии) и инвазионной (красные линии) частях ареалов, которые использовались для анализа перекрывания ниш. |

|

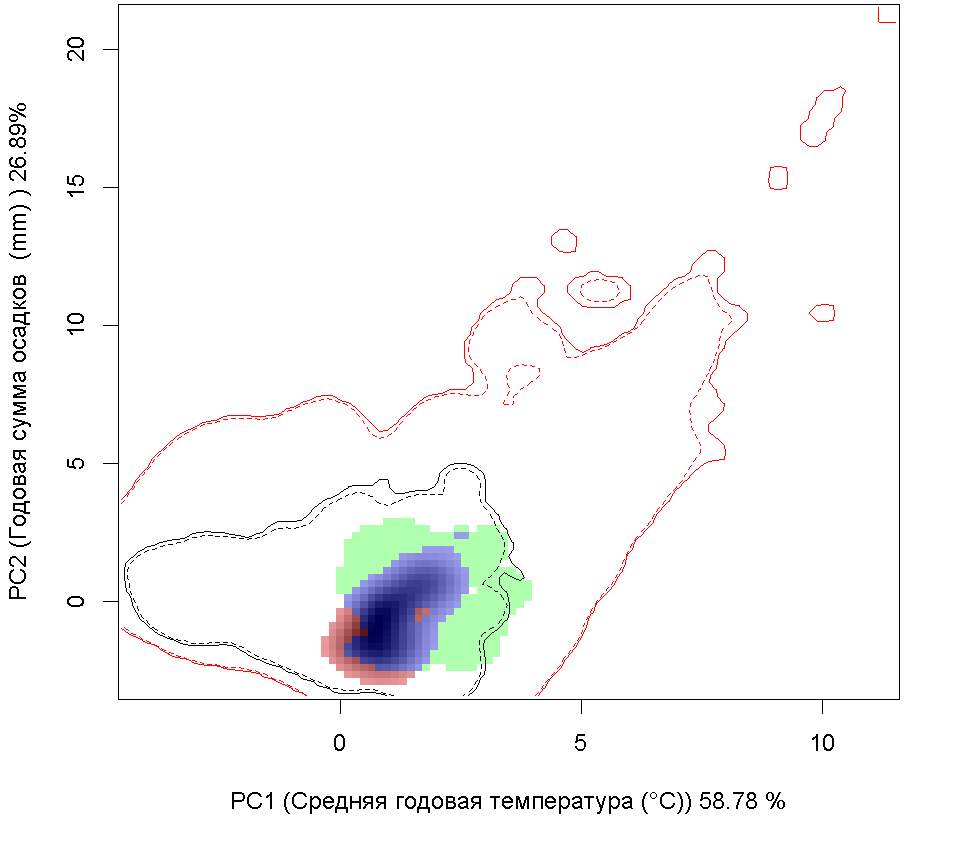

Сценарии изменения климата

|

|

RCP26

|

RCP45

|

|

C C

|

D D

|

|

RCP60

|

RCP85

|

|

E E

|

F F

|

| Графическое представление перекрывания ниш в условиях текущего климата и при сценариях его изменения - (C) RCP26; (D) RCP45; (E) RCP60; (F) RCP85. |

Литература

- Aldrich FA, 1961. Seasonal variations in the benthic invertebrate fauna of the San Joaquin River estuary of California, with emphasis on the amphipod, Corophium spincorne Stimpson. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 113:21-28.

- Alexandrov B, Boltachev A, Kharchenko T, Lyashenko A, Son M, Tsarenko P, Zhukinsky V, 2007. Trends of aquatic alien species invasions in Ukraine. Aquatic Invasions, 2(3):215-242.

- Allman GJ, 1844. Synopsis of the genera and species of zoophytes inhabiting the fresh waters of Ireland. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History including Zoology, Botany, and Geology, 13:328-331.

- Allman GJ, 1853. On the anatomy and physiology of Cordylophora, a contribution to our knowledge of the Tubularian zoophytes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 143:367-384.

- Arndt EA, 1984. The ecological niche of Cordylophora caspia (Pallas, 1771). Limnologica, 15(2):469-477.

- Arndt EA, 1989. Ecological, physiological and historical aspects of brackish water fauna distribution. Reproduction, Genetics and Distribution of Marine Organisms:327-338.

- Barnes RSK, 1987. Coastal lagoons of East Anglia, U. Journal of Coastal Research, 3(4):417-427.

- Barnes RSK, 1994. The Brackish-water Fauna of Northwestern Europe. Cambridge University Press, 287 pp.

- Bibbins A, 1892. On the distribution of Cordylophora in the Chesapeake estuaries, and the character of its habitat. Trans. Maryland Academy of Science, 1:213-228.

- Bij Vaate Ade , Jazdzewski K, Ketelaars HAM, Gollasch S, Velde Gder, 2002. Geographical patterns in range extension of Ponto-Caspian macroinvertebrate species in Europe. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 59:1159-1174.

- Blake CH, 1932. Cordylophora in Massachusetts. Science, 76(1972):345-346.

- Blezard DJ, 1999. Salinity as a refuge from predation in a nudibranch-hydroid relationship within the Great Bay estuary system. New Hampshire, USA: University of New Hampshire, 77 pp.

- Bouillon J, Gravili C, Pages F, Gili JM, Boero F, 2006. An introduction to Hydrozoa. Paris, : Publications Scientifiques du Museum Paris.

- Briggs EA, 1931. Notes on Australian athecate Hydroids. Records of the Australian Museum, 18:279-282.

- Calder DR, 1968. Hydrozoa of southern Chesapeake Bay. Virginia, USA: School of Marine Science, The College of William and Mary.

- Calder DR, 1971. Hydroids and hydromedusae of southern Chesapeake Bay. Virginia Institute of Marine Science Special Paper of Marine Science, 1:125.

- Calder DR, 1976. The zonation of hydroids along salinity gradients in South Carolina estuaries. In: Coelenterate ecology and behavior [ed. by Mackie GO] New York, : Plenum Press, 165-174.

- Calder DR, 1988. Shallow-water hydroids of Bermuda: the athecate. In: Royal Ontario Museum Publications in Life Sciences Toronto, Canada: University of Toronoto Press, 5-15.

- Calder DR, Kirkendale L, 2005. Hydroids (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) from shallow-water environments along the Caribbean coast of Panama. Caribbean Journal of Science, 41(3):476-491.

- Calmano W, Ahlf W, Bening JC, 1992. Chemical mobility and bioavailability of sediment-bound heavy metals influenced by salinity. Hydrobiologia, 235/236:605-610.

- Carlton JT, 1979. Introduced invertebrates of San Francisco Bay. In: San Francisco Bay: the urbanized estuary [ed. by Conomos TJ] San Francisco, : Pacific Division of the American Association for the Advancement of Science c/o California Academy of Science, 427-444.

- Carlton JT, 2009. Deep invasion ecology and the assembly of communities in historical time. In: Biological invasions in marine ecosystems. Ecological studies 204 [ed. by Rilov G, Crooks JA] Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 13-56.

- Cartwright P, Evans NM, Dunn CW, Marques AC, Miglietta MP, Schuchert P, Collins AG, 2008. Phylogenetics of Hdroidolina (Hydrozoa: Cnidaria). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 88:1663-1672.

- Cheruvelil KS, Soranno PA, Madsen JD, Roberson MJ, 2002. Plant architecture and epiphytic macroinvertebrate communities: the role of an exotic dissected macrophyte. Journal of North American Benthological Society, 21(2):261-277.

- Chester CM, Turner R, Carle M, Harris LG, 2000. Life history of a hydroid/nudibranch association:a discrete-event simulation. The Veliger, 43(4):338-348.

- Clarke SF, 1878. A new locality for Cordylophora. American Naturalist, 12:232-234.

- Cohen A, Carlton JT, 1995. Nonindigenous aquatic species in a United States estuary: a case study of the biological invasions of the San Francisco Bay and delta. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington DC and the National Sea Grant College Program, Connecticut Sea Grant. USA: NOAA, 1-251.

- Cohen A, Mills C, Berry H, Wonham M, Bingham B, Bookheim B, Carlton J, Chapman J, Cordell J, Harris L, Klinger T, Kohn A, Lambert C, Lambert G, Li K, Secord D, Toft J, 1998. A rapid assessment survey of non-indigenous species in the shallow waters of Puget Sound. Report of the Puget Sound Expedition September 8-16, 1998., 1-36.

- Cohen AN, 2006. Species introductions and the Panama Canal. In: Bridging divides: maritime canals as invasion corridors [ed. by Gollasch S, Galil BS, Cohen AN] Dordrecht, : Springer, 127-206.

- Cooke WJ, 1977. Order hydroida. Reef and Shore Fauna of Hawaii, Section 1: Protozoa through Ctenophora. Bishop Museum Special Publication, 64(10):71-104.

- Cory RL, 1967. Epifauna of the Patuxent River Estuary, Maryland, for 1963 and 1964. Chesapeake Science, 8(2):71-89.

- Cory RL, Nauman JW, 1969. Epifauna and thermal additions in the upper Patuxent River estuary. Chesapeake Science, 10(3):210-217.

- Cranfield HJ, Gordon DP, Willan RC, Marshall BA, Battershill CN, Francis MP, Nelson WA, Glasby CJ, Read GB, 1998. Adventive marine species in New Zealand. NIWA Technical Report., 1-48.

- Davis JR, 1980. Species composition and diversity of benthic macroinvertebrate populations of the Pecos River, Texas. Southwestern Naturalist, 25(2):241-256.

- Dean D, Haskin HH, 1964. Benthic repopulation of the Raritan River estuary following pollution abatement. Limnology and Oceanography, 9(4):551-563.

- Dean TA, Bellis VJ, 1975. Seasonal and spatial distribution of the epifauna in the Palmico River estuary, North Carolina. Journal of Elisha Mitchell Science Society, 91(1):1-12.

- Delong MD, Payne JF, 1985. Patterns of colonization by macroinvertebrates on artificial substrate samplers: the effects of depth. Freshwater Invertebrate Biology, 4(4):194-200.

- Devin S, Bollache L, Noel PY, Beisel JN, 2005. Patterns of biological invasions in French freshwater systems by non-indigenous macroinvertebrates. Hydrobiologia, 551:137-146.

- Dumont HJ, 2009. A description of the Nile Basin, and a synopsis of its history, ecology, biogeography, hydrology, and natural resources. Springer Science + Business Media B. In: The Nile: origin, envoronments, limnology and human use [ed. by Dumont HJ]: Springer Science + Business Media B.V., 495-498.

- El-Shabraway GM, Fisher MR, 2009. The Nile benthos. In: The Nile: origin, envoronments, limnology and human use [ed. by Dumont HJ]: Springer Science + Business Media B.V., 563-583.

- Fofonoff PW, Ruiz GM, Hines AH, Steves BD, Carlton JT, 2009. Four Centuries of Biological Invasions in Tidal Waters of the Chesapeake Bay Region (Chapter 28). In: Biological Invasions in Marine Ecosystems. Ecological Studies 204 [ed. by Rilov G, Crooks JA] Berlin, Heidelberg, : Springer-Verlag, 749-506.

- Folino NC, 2000. The freshwater expansion and classification of the colonial hydroid Cordylophora. In: Marine Bioinvasions: Proceedings of the First National Conference, Cambridge, MA, 24-27 January 1999: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sea Grant College Program, 139-144.

- Folino-Rorem NC, Berg MB, 2007. The impact of the invasive Ponto-Caspian hydroid, Cordylophora caspia, on Benthic Macroinvertebrate Communities in Southern Lake Michigan: Effects on Fish Prey Availability. In: 15th International Conference on Aquatic Invasive Species, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, September 23-27, 2007.

- Folino-Rorem NC, Darling JA, D'Ausilio CA, 2009. Genetic analysis reveals multiple cryptic invasive species of the hydrozoan genus Cordylophora. Biological Invasions.

- Folino-Rorem NC, Duggan MJ, Macdonald AP, Mindrebo EK, Berg MB, 2009. Distribution and diet of the invasive Ponto-Caspian hydroid, Cordylophora caspia, in southern Lake Michigan: potential effects on fish prey availability. In: 57th Annual Meeting of the North American Benthological Society, 17-22 May 2009, Grand Rapids, MI.

- Folino-Rorem NC, Indelicato J, 2005. Controlling biofouling caused by the colonial hydroid Cordylophora caspia. Water Research, 39:2731-2737.

- Folino-Rorem NC, Stoeckel J, 2006. Exploring the coexistence of the hydroid Cordylophora caspia and the zebra mussel Dreissena polymorpha: counterbalancing effects of filamentous substrate and predation. Aquatic Invaders, 17(2):8-16.

- Franzen A, 1996. Ultrastructure of spermatozoa and spermiogenesis in the hydrozoan Cordylophora caspia with comments on structure and evolution of the sperm in the cnidaria and the Porifera. Invertebrate Reproduction and Development, 29(1):19-26.

- Fraser CM, 1944. Hydroids of the Atlantic coast of North America. Toronto: The University of Toronto Press, 315 pp.

- Fulton C, 1962. Environmental factors influencing the growth of Cordylophora. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 151:61-78.

- Fyfe ML, 1929. A new fresh-water hydroid from Otago. Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute, 59:813-823.

- Galea HR, 2007. Cnidaria:Hydrozoa: latitudinal distribution of hydroids along the fjords region of southern Chile, with notes on the world distribution of some species. Check List, 3(4):308-320.

- Garman H, 1922. Fresh water coelenterate in Kentucky. Science, 56(1458):664.

- Gaulin G, Dill L, Beaulieu J, Harris LG, 1986. Predation-induced changes in growth form in a nudibranch-hydroid association. The Veliger, 28(4):389-393.

- Gollasch S, Rosenthal H, 2006. The Kiel Canal: the world's busiest man-made waterway and biological invasions. In: Bridging divides: maritime canals as invasion corridors [ed. by Gollasch S, Galil BS, Cohen AN] Dordrecht, : Springer, 5-90.

- Gosner KL, 1971. Guide to identification of marine and estuarine invertebrates: Cape Hatteras to the Bay of Fundy. New York, NY, : John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Goulletquer P, Bachelet G, Sauriau PG, Noel P, 2002. Open Atlantic coast of Europe-a century of introduced species into French waters. In: Invasive aquatic species of Europe: distribution, impacts and management [ed. by Leppakoski E, Gollasch S, Olenin] Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 276-290.

- Hamilton A, 1883. A fresh-water hydrozoon. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology, 1(9):419-420.

- Hargitt CW, 1924. Hydroids of the Philippine Islands. The Philippine Journal of Science, 24(4):467-507.

- Harris HG, Dijkstra J, 2007. Seasonal appearance and monitoring of invasive species in the Great Bay estuarine system. A Final Report to The New Hampshire Estuaries Project., 1-27.

- Havens KE, Bull GL, Crisman TL, Philips EJ, Smith JP, 1996. Food web structure in a subtropical lake ecosystem. Oikos, 75:20-32.

- Huang Z, Li C, Zhang L, Li F, Zheng C, 1981. The distribution of fouling organisms in the Changjiang River estuary. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinca, 12(6):531-537.

- Ito T, 1952. A new species of athecate hydroid Cordylophora from Japan. Special publication Japan Sea Region. Fishing Research Lab. Nanao:55-57.

- Jankowski T, Collins AG, Campbell R, 2008. Global diversity of inland cnidarians. Hydrobiologia, 595:35-40.

- Jenner HA, Whitehouse JW, Colin JL, Khalanski M, 1998. Cooling water management in European power stations: biology and control of fouling. Hydroecologie Appliquee, 10(1-2):225.

- Jensen KR, Knudsen J, 2005. A summary of alien marine benthic invertebrates in Danish waters. Oceanological and Hydrobiological Studies, 34(1):137-162.

- Jewett EB, 2005. Epifaunal disturbance by periodic low dissolved oxygen: native versus invasive species response. College Park, Maryland, : University of Maryland, 181 pp.

- Jones ML, Rutzler K, 1975. Invertebrates of the upper chamber, Gatun Locks, Panama Canal, with emphasis on Trochospongilla leidii (porifera). Marine Biology, 33(1):57-66.

- Jormalainen V, Honkanen T, Vuorisalo T, Laihonen P, 1994. Growth and reproduction of an estuarine population of the colonial hydroid Cordylophora caspia (Pallas) in the northern Baltic sea. Helgolander Meeresunters, 48:407-418.

- Josephson RK, 1961. Colonial responses of hydroid polyps. Journal of Experimental Biology, 38:559-577.

- Ketelaars HA, 2004. Range extensions of Ponto-Caspian aquatic invertebrates in continental Europe. In: Aquatic invasions in the Black, Caspian, and Mediterranean Seas [ed. by Dumont H] Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 209-236.

- Kinne O, 1956. [English title not available]. (Uber den Einfluss des salzgehaltes und der temperature auf wachstum, form, und vermehrung be idem hydroidpolypen Cordylophora caspia (Pallas), athecata, clavidae) Zool. Jb. (Physiol.), 66:565-638.

- Kinne O, 1958. Adaptation to salinity variations-some facts and problems. In: Physiological Adaptation [ed. by Prosser CL] Washington DC, : American Physiological Society, 92-106.

- Kinne O, 1971. Salinity: invertebrates. In: Marine Ecology [ed. by Kinne O] New York, : Wiley Interscience, 821-995.

- Leppakoski E, Gollasch S, Gruska P, Ojaveer H, Olenin S, Panov V, 2002. The Baltic-a sea of invaders. Canadian Journal of Fishing and Aquatic Science, 59:1175-1188.

- Leppakoski E, Shiganova T, Alexandrov B, 2009. European enclosed and semi-enclosed seas. In: Biological invasions in the marine ecosystems [ed. by Rilov G, Crooks JA] Berlin, : Springer, 529-547.

- Lesh-Laurie GE, 1972. Cordylophora morphogenesis: precocious sporosac development in non-sessile colonies. Journal of Marine Biology Association UK, 52:191-201.

- Massard JA, Geimer G, 1987. [English title not available]. (Note sur la presence de l'hydrozoaire Cordylophora caspia (Pallas, 1771) Dans la Moselle allemande et luxembourgeoise) Societe des Naturalistes Luxembourgeois Bulletin, 87:75-83.

- Matern SA, Brown LR, 2005. Invaders eating invaders: exploitation of novel alien prey by the alien shimofuri goby in the San Francisco Estuary, California. Biological Invasions, 7:497-507.

- Mills C, 1998. Commentary on species of Hydrozoa, Scyphozoan, and Anthozoa (Cnidaria) sometimes listed as non-indigenous in Puget Mills C, Rees JT, 2000. New observations and corrections concerning the trio of invasive hydromedusae Maeotias marginata (=M. inexpectata), Blackfordia virginica, and Moerisia sp. in the San Francisco estuary. Scientia Marina, 64(1):151-155.

- Mills EL, Leach JH, Carlton JT, Secor CL, 1993. Exotic species in the Great Lakes: a history of biotic crises and anthropogenic introductions. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 19:1-54.

- Mills EL, Strayer DL, Scheuerell MD, Carlton JT, 1996. Exotic species in the Hudson River basin: a history of invasions and introductions. Estuaries, 19(4):814-823.

- Musko IB, Bence M, Balogh CS, 2008. Occurance of a new ponto-caspian invasive species, Cordylophora caspia (Pallas 1771) (Hydrozoa: Clavidae) in Lake Balaton (Hungary). Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 54(2):169-179.

- Naumov DV, 1969. Hydroids and hydromedusae of the USSR. In: Keys to the Fauna of the USSR [ed. by Pavlovskii EN, Bykhovskii BE, Vinogradov BS, Strelkov AA, Shtakel'berg AA]: Zoological Institute of the Academy of Science of the USSR, 1-197.

- Nehring S, 2006. Four arguments why so many alien species settle into estuaries, with special reference to the German river Elbe. Helgoland Marine Research, 60(2):127-134. http://www.springerlink.com/(vbc5i445bmwdkp45y4ynpj45)/app/home/contribution.asp?referrer=parent&backto=issue,9,13;journal,2,169;linkingpublicationresults,1:103796,1

- NOBANIS, 2011. North European and Baltic Network on Invasive Alien Species. http://www.nobanis.org/

- Nutting CC, 1901. The hydroids of the Woods Hole region. Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission, 19:325-386.

- Paavola M, Olenin S, Leppakoski E, 2005. Are invasive species most successful in habitats of low native species richness across European brackish water seas? Estuarine,Coastal and Shelf Science, 64:738-750.

- Pienimaki M, Leppakoski E, 2004. Invasion pressure on the Finnish Lake District: invasion corridors and barriers. Biological Invasions, 6:331-346.

- Pinder AM, Halse SA, McRae JM, Shiel RJ, 2005. Occurance of aquatic invertebrates of the wheatbelt region of Western Australia in relation to salinity. Hydrobiologia, 543(1):1-24.

- Porrier MA, Denoux GJ, 1973. Notes on the distribution, ecology, and morphology of the colonial hydroid Cordylophora caspia (Pallas) in southern Louisiana. Southwestern Naturalist, 18(2):253-255.

- Rajagopal S, velde GDer , Ven Gaag MDer , Jenner HA, 2002. Labratory evaluation of the toxicity of chlorine to the fouling hydroid Cordylophora caspia. Biofouling, 18:57-64.

- Ringelband U, Karbe L, 1996. Effects of vanadium on population growth and Na-K-ATPase activity of the brackish water hydroid Cordylophora caspia. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 57:118-124.

- Roca I, 1987. Hydroids on posidonia in Majorcan waters. Modern Trends in the Systematics, Ecology and Evolution of Hydroids and Hydromedusae:209-214.

- Roch F, 1924. [English title not available]. (Experimentelle untersuchungen an Cordylophora caspia (Pallas) [=Lacustris Allman] uber die abhangigkeit ihrer geographischen verbreitung und ihrer wuchsformen von den physikalischchemischen bedingungen des umgebenden mediums. Z. morph. okol) Tierre, 2:350-426.

- Roos PJ, 1979. Two-stage life cycle of a Cordylophora population in the Netherlands. Hydrobiologia, 62(3):231-239.

- Roque FO, Trivinho S, Jancso M, Fragoso EN, 2004. Record of chironomidae larvae living on other aquatic animals in Brazil. Biota Neotropica, 4(2):1-9.

- Rose PG, Burnett AL, 1969. The origin of mucous cells in hydra viridis. Development Genes and Evolution, 165(3):177-191.

- Ruiz GM, Fofonoff P, Carlton J, Wonham MJ, Hines AH, 2000. Invasion of coastal communities in North America: apparent patterns, processes, and biases. Annual Review of Ecological Systematics, 31:481-531.

- Ruiz GM, Fofonoff P, Hines AH, 1999. Non-indigenous species as stressors in estuarine and marine communities: assessing invasion impacts and interactions. Limnological Oceanography, 44(3, part 2):950-972.

- Rz?ska J, 1949. Cordylophora from the Upper White Nile. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 12th series, 2(19):558-560.

- Schmitt WL, 1927. Additional records of the occurrence of the fresh-water jelly-fish. Science, 66(1720):591-593.

- Schuchert P, 2007. The European athecate hydroids and their medusae (Hydrozoa, Cnidaria): filfera part 2. Revue Suisse de Zoologie, 114(2):195-396.

- Shokin IV, Nabozhenko MV, Sarvilina SV, Titova EP, 2006. The present-day condition and regularities of the distribution of the bottom communities in Taganrog Bay. Oceanology, 46(3):401-410.

- Siegfried CA, Kopache ME, Knight AW, 1980. The benthos portion of the Sacramento River (San Francisco Bay Estuary). Estuaries, 3(4):296-307.

- Smith DG, 1989. Keys to the freshwater macro invertebrates of Massachusetts (No. 4): Benthic colonial phyla, including the Cnidaria, Entoprocta, and Ectoprocta. Westborough, Massachusetts, : The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Technical Services Branch, Division of Water Pollution Control.

- Smith DG, 2001. Pennak's freshwater invertebrates of the Untied States: Porifera to Crustacea. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons Inc, 638 pp.

- Smith DG, Werle SF, Klekowski E, 2002. The rapid colonization and emerging biology of Cordylophora caspia (Pallas, 1771) (Cnidaria: Clavidae) in the Connecticut River. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 17(3):423-430.

- Smith F, 1910. Hydroids in the Illinois River. The Biological Bulletin, 18:67-68.

- Smith F, 1918. Hydra and other fresh-water Hydrozoa. In: Fresh Water Biology [ed. by Ward HB, Whipple GC] New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Stepanjants SD, Timoshkin OA, Anokhin BA, Napara TO, 2000. A new species of pachycordyle (hydrozoa, clavidae) from Lake Biwa (Japan), with remarks on this and related clavid genera. Scientia Marina, 64(1):225-236.

- Strayer DL, Malcom HM, 2007. Submersed vegetation as habitat for invertebrates in the Hudson River estuary. Estuaries and Coasts, 30(2):253-264.

- Streftaris N, Zenetos A, Papathanassiou E, 2005. Globalisation in marine ecosystems: the story of non-indigenous marine species across European seas. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, 43:419-453.

- Tessnow W, 1959. [English title not available]. (Untersuchungen an den interstitiellen Zellen von Pelmatohydra oligactis Pallas und Cordylophora caspia Pallas unter besonder Berucksichtigung spezifischer Farbemethoden) Protoplasma, 51(4):563-594.

- Vanderploeg HA, Nalepa TF, Jude DJ, Mills EL, Holeck KT, Liebig JR, Girgorovich IA, Ojaveer H, 2002. Dispersal and emerging ecological impacts of Ponto-Caspian species in the Laurentian Great Lakes. Canadian Journal of Fishing and Aquatic Science, 59:1209-1228.

- Venkastesan R, Murthy PS, 2008. Macrofouling control in power plants. In: Marine and Industrial Biofouling [ed. by Flemming HC, Murthy PS, Venkatesan R, Cooksey K] Berlin, : Springer, 265-291.

- Verrill AE, Smith SI, Harger O, 1873. Catalog of the marine invertebrate animals of the southern coast of New England. Report of the United States Fish Commission, 1872(8):537-77.

- Vervoort W, 1964. Note on the distribution of Garveia franciscana (torrey, 1902) and Cordylophora caspia (Pallas, 1771) in the Netherlands. Zoologische Mededelingen, 39:125-146.

- Warfe DM, Barmuta LA, 2004. Habitat structural complexity mediates the forging success of multiple predator species. Oecologia, 141:171-178.

- Wasson K, Fenn K, Pearse JS, 2005. Habitat differences in marine invasions of central California. Biological Invasions, 7:935-948.

- Weise JG, 1961. The ecology of Urnatella gracilis Leidy: phylum Endoprocta. Limnology and Oceanography, 6(2):228-230.

- Wolff WJ, 1999. Exotic invaders of the meso-oligohaline zone of estuaries in the Netherlands: why are there so many? Helgolander Meeresunters, 52:393-400.

- Wonham MJ, Carlton JT, 2005. Trends in marine biological invasions at local and regional scales: the Northeast Pacific Ocean as a model system. Biological Invasions, 7:369-392.

- Zaiko A, Olenin S, Daunys D, Nalepa T, 2007. Vulnerability of benthic habitats to the aquatic invasive species. Biological Invasions, 9:703-714.

Другие ссылки

http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=117428

http://invasions.si.edu/nemesis/calnemo/SpeciesSummary.jsp?TSN=48893

http://fish.kiev.ua/pages/givotm/givotm24.htm